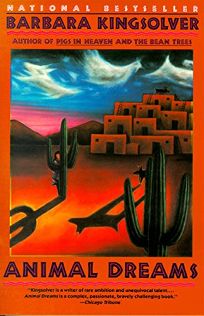

Sometimes, especially when I'm stressed, I can't deal with reading a new book, or I just want the comfort of something I've read before. Maybe a few times before. Animal Dreams is one of my favorite books, one of the few I keep a hard copy of. It's the first book of Kingsolver's I ever read, and I went on to read all of her previous prose and kept up with her new books as along as I could. I struggled through The Poisonwood Bible and Prodigal Summer and finally gave up on Animal, Vegetable, Mineral. After rereading Animal Dreams for the fifth-ish time, which I love SO MUCH, I need to give her new books another try. We meet Codi Noline as she returns to the tiny Arizona town she grew up in, a place she never felt home. She's called back because her father's behavior has moved from eccentric to demented (medically--he's starting to show signs of Alzheimer's). Despite being back in the place that formed her, Codi feels rootless without her younger sister Hallie, who is also her best friend, co-conspirator, and hero. It is the late 1980s, and Hallie has gone to Nicaragua to prepare the ground for revolution--she's a plant specialist. Codi's story, reconnecting to her past, while longing for the only thing she thinks she can relate to, is powerfully effecting. She's smart and charming, but flawed. The people around her are warm and believable, including her best friend Emelina; Loyd, Codi's sole high school boyfriend, who is now working on the railroad with Emelina's husband, Loyd's dog Jack, and the colorful town elders, known as the Stitch and Bitch club. Codi's dad has a lot going on, too, but he's not exactly warm. He might want to be, but it doesn't seem to be in him. Codi, either. I sobbed through much of my rereading, more than in previous reads I think, maybe because of my stress level, but oh, I love these characters and appreciate the political subthemes--greedy corporations destroying the environment, US funded death squads, and indigenous traditions explained and filtered through an Indian boy who lost his twin. I also love Kingsolver for her love of libraries. Before Hallie leaves for Nicaragua, she tells Codi to make sure she returns Hallie's overdue library book. "Take it back and pay the fine, okay? Libraries are the one American institution you shouldn't rip off." It's clear Hallie doesn't think much of American institutions, so this is a generous statement. I'd forgotten this example I use on xenophobic people who think all religions other than their own are superstitious nonsense came from AD:

Sometimes, especially when I'm stressed, I can't deal with reading a new book, or I just want the comfort of something I've read before. Maybe a few times before. Animal Dreams is one of my favorite books, one of the few I keep a hard copy of. It's the first book of Kingsolver's I ever read, and I went on to read all of her previous prose and kept up with her new books as along as I could. I struggled through The Poisonwood Bible and Prodigal Summer and finally gave up on Animal, Vegetable, Mineral. After rereading Animal Dreams for the fifth-ish time, which I love SO MUCH, I need to give her new books another try. We meet Codi Noline as she returns to the tiny Arizona town she grew up in, a place she never felt home. She's called back because her father's behavior has moved from eccentric to demented (medically--he's starting to show signs of Alzheimer's). Despite being back in the place that formed her, Codi feels rootless without her younger sister Hallie, who is also her best friend, co-conspirator, and hero. It is the late 1980s, and Hallie has gone to Nicaragua to prepare the ground for revolution--she's a plant specialist. Codi's story, reconnecting to her past, while longing for the only thing she thinks she can relate to, is powerfully effecting. She's smart and charming, but flawed. The people around her are warm and believable, including her best friend Emelina; Loyd, Codi's sole high school boyfriend, who is now working on the railroad with Emelina's husband, Loyd's dog Jack, and the colorful town elders, known as the Stitch and Bitch club. Codi's dad has a lot going on, too, but he's not exactly warm. He might want to be, but it doesn't seem to be in him. Codi, either. I sobbed through much of my rereading, more than in previous reads I think, maybe because of my stress level, but oh, I love these characters and appreciate the political subthemes--greedy corporations destroying the environment, US funded death squads, and indigenous traditions explained and filtered through an Indian boy who lost his twin. I also love Kingsolver for her love of libraries. Before Hallie leaves for Nicaragua, she tells Codi to make sure she returns Hallie's overdue library book. "Take it back and pay the fine, okay? Libraries are the one American institution you shouldn't rip off." It's clear Hallie doesn't think much of American institutions, so this is a generous statement. I'd forgotten this example I use on xenophobic people who think all religions other than their own are superstitious nonsense came from AD:

"I thought a kachina was a little doll." "That's right." "And also a person dressed up?" "Yep. And a spirit." "A spirit with a family and a mailing address." "That's right. When the person dresses up a certain way, the spirit comes into him. And into the doll, if it's made right." "Okay," I said. "What?" "Nothing, just okay. I understand." He smiled at me sideways. "You think it sounds voodoo?" "All right, I'm narrow-minded. It sounds kind of voodoo." We both paid attention to the dancers for a while. I needed to keep a little distance from Loyd. "Anglos put little dolls of Santa Claus around their houses at Christmas," Loyd said without looking at me. "Yeah, but it's just a little doll." "And does it have a wife?" "Yes," I conceded. "A wife and elves. And they live at the North Pole." "And sometimes one guy will dress up like Santa Claus. And everybody acts a certain way when he comes around. All happy and generous." I'd never been put in a position to defend Santa Claus. I'd never even believed in Santa Claus. "That's just because he stands for the spirit of Christmas," I said. "Exactly." Loyd seemed very pleased with himself. One of the hunters had drawn his bow and shot an invisible arrow into a deer. It gave an anguished shiver, and then the other hunters lifted its limp carcass onto their shoulders. "I've seen Jesus kachinas too," Loyd said. "I've seen them hanging all over people's houses in Grace."

(text grabbed from Kobobook.net) Hallie, who we don't get to spend a lot of time with, is a smarty and maybe an anarchist. She writes in a letter, "Wars and elections are both too big and too small to matter in the long run. The daily work-that goes on, it adds up. It goes into the ground, into crops, into children's bellies and their bright eyes. Good things don't get lost." I don't know when I'll reread Animal Dreams again, but I won't let it get lost.