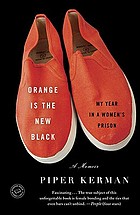

I'm a little afraid to proclaim how much I enjoyed this middle class white lady prison memoir for fear that my prison justice activist friends will tell me everything that's wrong with it. Regardless, Orange Is the New Black is a really good read. In Smith alumna Piper Kerman tells of her experiences doing time for a drug crime committed over ten years before her incarceration. It's not a woe is me (or woe is I) story. She fully cops to her crime and in fact prison does educate her on just how deleterious drug trafficking is when she understands her fellow inmates' addictions and plights. She isn't uncritical, though, of the "war on drugs."

I found this passage to be thoughtful and accurate.

Before she reports to prison, her attorney warns her that the hardest part of her time will be abiding by petty and indifferent prison officials. She learns how true that is her first week, and how dangerous for someone in worse health than she.

"But worst of all was the woman from health services, who was so unpleasant that I was taken aback. She firmly informed us that we had better not dare to waste their time, that they would determine whether we were sick or not and what was medically necessary, and that we should not expect any existing condition to be addressed unless it was life-threatening. I silently gave thanks that I was blessed with good health. We were fucked if we got sick." p.53

and

"It is hard to conceive of any relationship between two adults in America being less equal than that of prisoner and prison guard. The formal relationship, enforced by the institution, is that one person's word means everything and the other's means almost nothing; one person can command the other to do just about anything, and refusal can result in total physical restraint. ... Even in relation to the people who are anointed with power in the outside world--cops, elected officials, soldier--we have rights within our interactions. We have a right to speak to power, though we may not exercise it. But when you step behind the walls of a prison as an inmate, you lose that right. It evaporates, and it's terrifying. And pretty unsurprising when the extreme inequality of the daily relationship between prisoners and their jailers leads very naturally into abuses of many flavors, from small humiliations to hideous crimes." p. 129-130

Except for her last two or three months, after being transferred to testify in a trial, she doesn't portray her time as that hard. The difficulties were mostly in missing her loved ones and feeling horribly guilty for what she put them through. She even compares life in the prison dorm to that in a women's college.

"At Smith College the pervasive obsession with food was expressed at candlelight dinners and at Friday-afternoon faculty teas; in Danbury it was via microwave cooking and stolen food. In many ways I was more prepared to live in close quarters with a bunch of women than some of my fellow prisoners, who were driven crazy by communal female living. There was less bulimia and more fights than I had known as an undergrad, but the same feminine ethos was present--empathetic camaraderie and bawdy humor on good days, and histrionic drams coupled with meddling, malicious gossip on bad days."

My main worry about a book like this one, from a social justice perspective, is that people will feel like they've done their part just by reading it. It would be great if each copy was issued with Vikki Law's Resistance behind Bars: the Struggles of Incarcerated Women, so that they could get an idea of what prison is like for what I assume is the majority of women prisoners. Kerman's time was relatively easy not only because she was blessed with good health, but also because her blond hair and blue eyes elicited sympathy from some of those in power over her. Being educated and smart helped her get decent positions in jail and articulate her case well when she needed to change jobs. She was in her 30s and secure in the love of her family and friends, which has to have an impact on her ability to have positive interactions with others. I don't want to be all down on Kerman because of her privilege, though. It sounds to me like she got a lot of her relationships with her fellow inmates and gave a lot in return, not just because of her privilege, but because she was a nice person with a good personality.

She talks about race issues, but doesn't make a big deal of them, and the same with other topics that could potentially get more preachy than sincere. I surely would have fallen into that trap. The strength of the memoir is that she keeps it real. The weakness is that there was no epilogue. I am seriously pained not to know if she kept up her friendships with her bunkie and dormmates.

No one who worked in "corrections" appeared to give any thought to the purpose of our being there, any more than a warehouse clerk would consider the meaning of a can of tomatoes, or try to help those tomatoes understand what the hell they were doing on the shelf. p.293