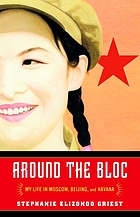

An aspiring journalist ca. 1990 attending a high school journalism camp queried the keynote on what to do to become a foreign correspondent. He (I think it was a he) responded, "Learn Russian." So that is what the Tex-Mex teen set out to do, and that's how she ended up in Moscow for about a year. Hers is a coming-of-age political memoir of a lefty journalist trying to sort out Revolution and her own identity. Well, the identity part sort of came last. She had to visit lots of foreign countries before she realized there were some important things she needed to learn about her own culture.

We follow Stephanie to Moscow where she has some trying times in a fly-infested student dorm, then to Beijing where she has a fellowship translating Chinese English to native English for an English language propaganda paper, and finally on a spontaneous trip to Havana. In each place she contemplates the politics and culture with and impressively open mind. She has her questions and criticisms, but by talking to the people, listening, and resisting as best she can the urge to impose her own values, she comes up with some really nuanced analyses of the various regimes, while at the same time remaining critical. I'd be really curious what my Cubaphile friends think of the Havana section.

These two quotes give you some idea of what I'm talking about:

"Throughout my travels around the Bloc, I wrestled with the question of whether each nation's respective Revolution had been worth the Struggle. Was the end to imperial practices like female foot binding, the eradication of diseases like leprosy, and the building of schools and hospitals throughout the People's Republic of China worth the senseless deaths of so many millions to state-induced famines, political purges, and labor camps? Was the privilege of living in a major industrialized nation and world superpower worth the terror and oppression of the Soviet Union? If not, why the hell did so many Russians and Chinese reflect their Revolutions with such nostalgia and continue to revere the men who led them? Were hundreds of millions of people living in total denial?

"Cuba complicated matters even further. One set of statistics revealed that it was one of the wealthiest nations in Latin America prior to the Revolution and became one of the poorest afterward. That unknown thousands of Cubans had drowned in the sea while trying to escape on rafts constructed of tires and plywood. But other stats told how postrevolutionary Cuba became the first underdeveloped country in the world to totally wipe out hunger and malnutrition. How Fidel's public health care system was recommended a 'model for the world' by the World Health Organization in in 1989 and how in literacy Cuba leads not only Latin America, but the United States as well." p 335

"If you ask a Cuban [about the Revolution], their knee-jerk reaction is to complain about the bureaucracy, the lack of efficiency, the shortage of goods. But if you sit down and really talk with them, you'll find that deep down, they still believe the Revolution is the best thing for Cuba." p. 354

And maybe also the fact that she lost her vegetarianism during her first meal in China. A strict vegetarian and relaxed vegan myself, I still found that funny and sympathetic.

I also love that the book has notes and an index.

Comments

Rebecca (not verified)

Mon, 06/14/2010 - 8:16am

Permalink

Hm, thanks for the rec! Might

Hm, thanks for the rec! Might have to read this. My summer project (well one of them) is to learn more about Communism *outside* the USSR, which (the USSR I mean) is all the historians of "international Communism" ever seem to write about....

I also love that it has notes and an index.